I never thought I’d start writing about my travels, though after coming back from a short trip to Phnom Penh, Cambodia I feel the need to sit down and put some thoughts on paper. It’s not what you’d normally expect from a ‘travel blog’: no food recommendation, beautiful beaches and cocktail bars to visit (though there’s plenty). The right category could be ‘horrors of history’ or ‘crazy stuff that few people know about’. If you bear with me, there might be also something optimistic towards the end.

Disclaimer: it’s not for everyone; if you feel particularly sensitive stop reading now.

Cambodia… where?

If you’re from Europe like me, Cambodia is one of those countries that is quite difficult to place on a map. Some people won’t even know it’s in Asia (yes it’s that bad), and if you asked me 10 years ago I would have hesitated too. Its famous neighbours take most of the spotlight: Thailand for the beautiful beaches and exotic dreams, and Vietnam for the war that took a solid place in people’s collective imagination and school’s history books.

It’s in those high school books that I read about Vietnam, and of course the many American movies making sense of one of their dark chapters of history. Something else, however, took almost no space in the books I read as a teen. At best it was a footnote or a short side chapter: Pol Pot.

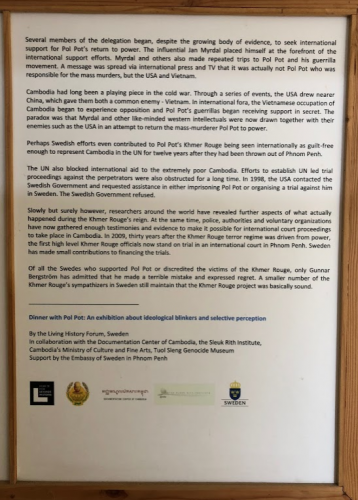

What a peculiar name. Short, snappy, fun-sounding, if you didn’t know better you could guess a cartoon character for kids (Pol Pot and Peppa Pig?), definitely not something you’d associate to the worst dictators in history: Hitler, Stalin, and… Pol Pot. Yet that’s where it deeply belongs.

A bit of history

I think it’s worth covering some facts – as some are largely unknown.

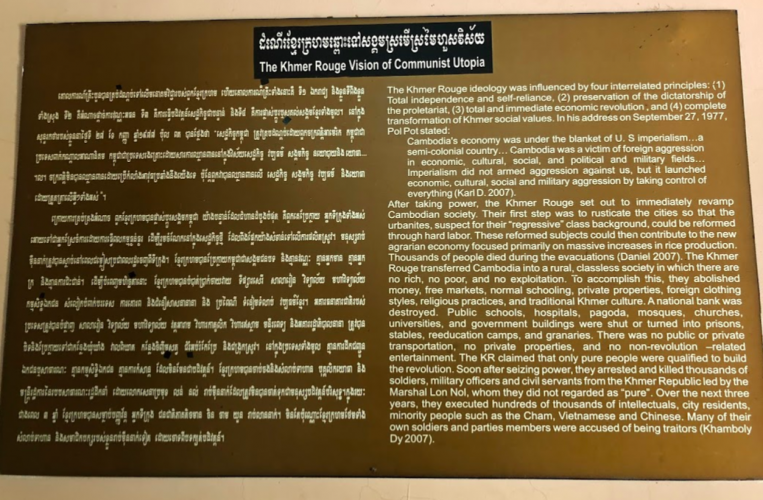

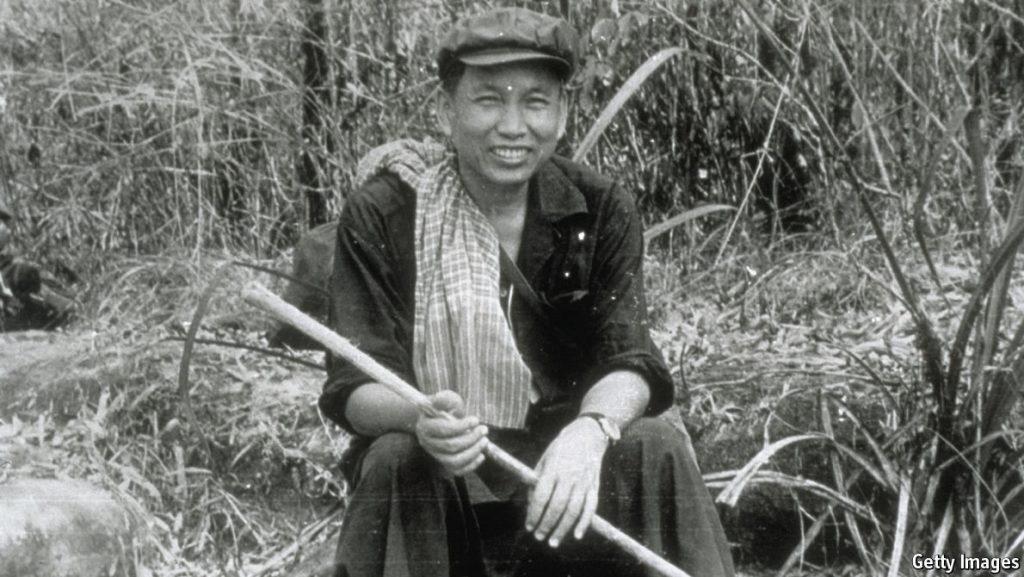

In 1975 the capital of Cambodia was under a military government, a corrupt regime under Lon Nol, which had the support of the USA*. Not a great government, though we know it was surely better than what was coming next. Bad decisions from the US (e.g. bombing Cambodia next to its Vietnam border to interrupt enemy supply lines), a difficult history and other complex factors led to a very unhappy population, understandably. That’s why, tired and looking for a change, many Cambodians welcomed the communist group called “Khmer Rouge” when they marched on Phnom Penh in April 1975.

Armed with weapons provided by the Chinese, they promised to free the country and give it back to its people: after all, khmer was the name of the Cambodian ethnicity, rouge is red as a communist symbols, coming to help the poor and free them up from imperialism and injustice.

Like in most revolutions, they were empty promises and many innocent people were about to pay the hefty price.

The rebel’s criminal nature didn’t wait long to show up. Cambodians in Phnom Penh couldn’t finish clapping and celebrating the newfound “freedom”, as they were immediately told they had to leave their homes. Not in months or weeks. Now. The “you have few minutes to grab your stuff or I’ll shoot you” kind of now. The whole capital city of Phom Penh was fully vacated in 3 days, with people migrating by foot, with almost no possessions. They were told that USA air forces were about to bomb the city, so it was just a matter of days, for their own safety, and they would come back soon.

Except there was no coming back. Their journey lasted years, if they weren’t killed or died of hunger and abuse.

Not many knew at the time, but that was fully part of the evil plot, a murderous design coming off the minds of Pol Pot and his small crew. At the basis of their ideology there was an intellectual idea of purity, an ideal vision of man, where farmers and field workers were the pure and uncorrupted natural state: “old men” as they called them. These were threatened by civilisation, imperialism, capitalism, corrupting them and building weak “city people”, educated members of a hated society.

It’s only the next logical step then to kick everyone out of the city and deeply revolutionise the social structure. Sadly ironic to note that Pol Pot studied radio engineering in Paris before falling in love with Marxism and Maoism.

The ideas of “social engineering” have been a common thread of the 20th century. My suspicion is that it comes from an industrial mentality (“if I can optimise the factory production line I can certainly do it with society”) and follows a thought process that roughly goes like this:

- Society is unjust (who can disagree, at any time in history?)

- The fault falls entirely on X (imperialism, capitalism, Jews, Armenians, the royalty etc.. take your pick)

- If only we got rid of X we’d finally be happy

- We have a plan to do so, and everyone needs to follow (or else they’re part of the main problem)

It usually requires massive arbitrary killings and infinite amounts of suffering. And Cambodia was no exception.

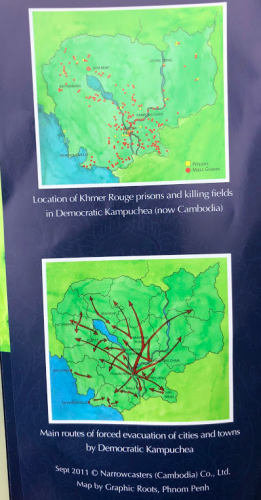

Cambodians were never allowed back to the cities. Instead, forced mass migration scattered the entire population across the country.

Picture yourself there. If you were not dead by the time you reached the next arbitrary destination with no food and water, you would likely end up in a work camp next to a farming field – separated from most of your family. At numerous militarised checkpoints you’d be abandoning all of your possessions (“the revolution needs them”), except the clothes you had on – which had to be tainted black, as everybody needed to be the same. If you were clearly educated, had “fancy” possessions like a watch or looked like a mid-level employee at a bank, you’d be called aside and killed. If you weren’t a clear revolution enemy from day one, you’d be filtered in different groups according to your physical capabilities: either sent to a farming field or to a military training camp.

And this was just the first week. Anholes even worst nightmare was unveiled early on, and that’s one of the things that surprised me the most: the insane speed of execution of a weird self destroying plan.

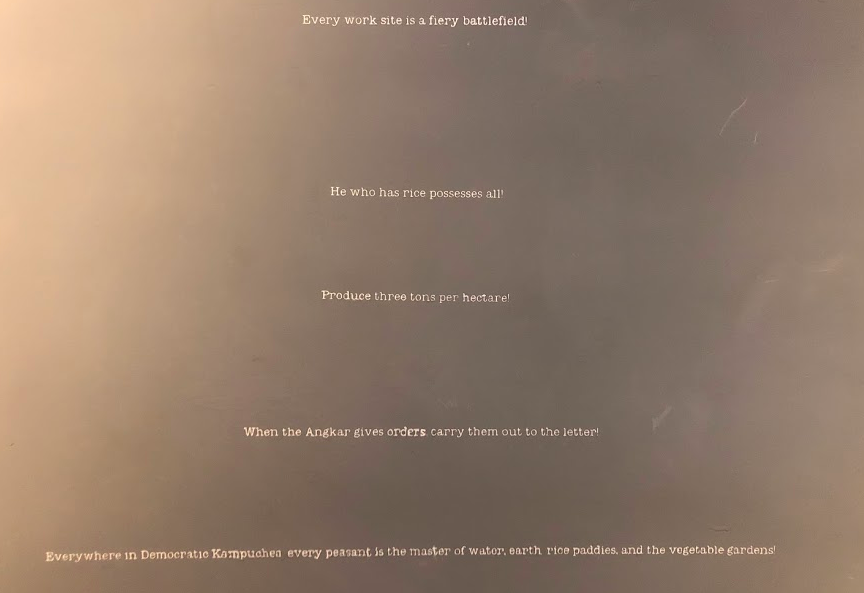

Why do I say weird? Since the beginning of the revolution, people were forced to make sacrifices to support “the Angkar”, literally “the Organisation” – like something out of a Orwell book. First, the house and clothes. Then all private property, any possession, from a watch to food, to a picture of your family. Even your own family had the sole purpose to serve Angkar. People belonged to it. Either to support the revolution by fighting, or farming to provide food to fighters.

No one knew what the Angkar was, or who was in power (which is even crazier), just that it was unforgiving. Any hesitation towards the guards, questioning authority or being slow in executing orders would suffer immediate deadly consequences. It would take just the smallest suspicion to be convicted of “conspiracy”. And the death sentence for anyone would extend to their entire family. Pol Pot used to say: “It’s better to kill ten innocent victims than to let one guilty person go free.”

That created a toxic culture of despair, lack of trust, deep fear in others, anonymous delations. The paranoia was so high that no one was ever safe. Even multiple members of the revolutions were tortured and killed. A relentless witch hunt.

- Soft hands? Soft person, a member of the capitalist regime. Killed.

- Wearing Glasses? An intellectual, a capitalist threat. Killed.

- A doctor? A teacher? A priest? Even worse, parasites and corruptors. Killed.

- Unable to keep up with rice production? Delaying to execute orders? Taking more food that two spoons of rice a day? Same fate. Almost anything could mean the end of your life.

The murdering spree was so methodical and deliberate that it’s hard to comprehend. The country was immediately closed to the outside world, making it difficult to gather any kind of news (think about North Korea now, but worse). For a long time, many outsiders believed that finally Cambodia was given “back to its people”.

The Khmer government even sent cries for help to its expatriates: something like “we’re rebuilding our country and need your help, fellow countrymen”. Many patriots got back, keen to help. It was a trap. They were abroad, so they would have been “intellectuals” after all: sent to torture prisons and to killing camps.

In a few months you wouldn’t recognise the country. Empty cities. No hospitals, no schools, no transportation, no medicines. Child soldiers were soon planting landmines and chanting odes to the new “democratic Kampuchea”, the new country name. With private property abolished and religion banned, the survivors were left training to fight for the revolution or planting rice, with the objective to triple production in one year.

Of course it was an impossible goal, made especially so with a untrained, starving workforce. Very soon it led to famine, economic crisis, which drove more paranoia from the Khmer rouge, more killings, and more famine.. In an ever growing vicious cycle.

In the 4 years of Pol Pot’s power, ~25% of the country population died.

As I know how statistics can be dry, I think it’s worth to let it simmer. One person out of four. Statistically speaking, every single family would’ve lost at least a parent or child. To make it feel even more real, you could walk down the street of a city and imagine counting people: 1, 2, 3, dead. 1, 2, 3, dead… for everyone in an entire country. It’s unbelievable.

Back to the trip.

As a foreigner, it’s difficult to find any trace of this history across the country. Especially out of the capital: millions visit the beautiful Siem Reap without having any idea about it. It feels like a hidden secret. And really, it was Cambodians killing Cambodians, including family members and friends turning against each other.. I imagine it’s not a past to be comfortable about, just like with Hitler and Mussolini, but maybe even worse… One of the survivors told me that with private property gone, and an almost non existing justice system, most of the Khmer leadership were able to get rich with the new Vietnamese government, confiscating properties of others, getting in power etc.. nasty stuff

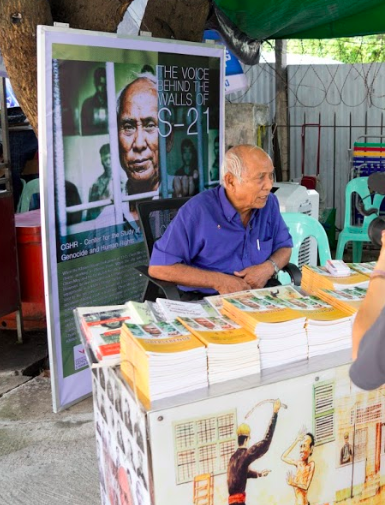

There a few ways you can now witness this past in Phnom Penh: the S21 prison, and the killing fields. Their stories are connected, despite being far apart. Both could be seen in one day if you wanted to.

S-21 (Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum)

Before turning into hell on earth, I imagine this being quite a beautiful school, made of few 3-stories buildings, surrounding a very large courtyard, a grass field with some beautiful trees, including big mangoes and other fruits. All classrooms have their entrance facing the courtyard, and I can imagine the kids loud noise and happiness when coming out for a break to play in the green fields. The contrast is stark once you see how the Khmer rouge ‘repurposed’ the school.

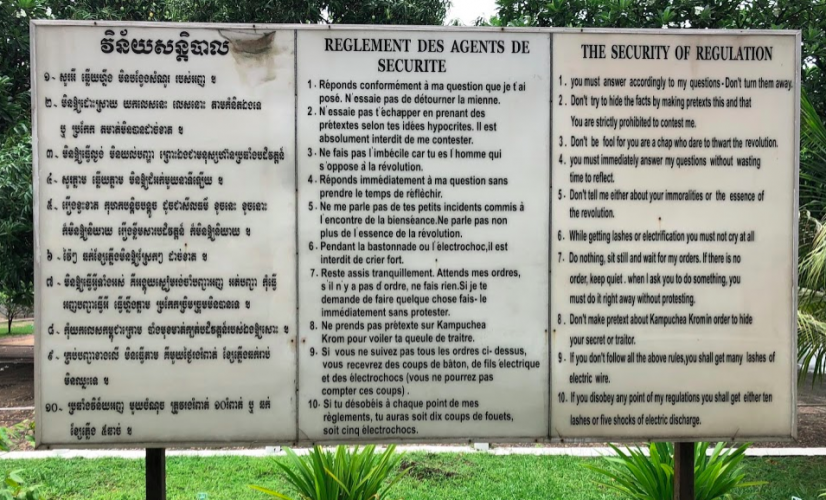

Barbed wire surrounded every building, windows and doors were shut, and dark classrooms were now turned into tiny prisons and torture rooms. With traces of school lessons still on the chalkboard, that place of joy and early life potential became an anteroom for death. Empty metal beds were placed in the middle of the classrooms, on which suspects were tied up to and tortured until they’d reach a “confession”. Guards would then record the confession sitting on the teachers desk, with meticulous precision, and the “guilty”, broken in body and spirit would be sent for killing. No one came out of S21 as an innocent. Confessions were extracted through unimaginable pain. As the regime became more and more paranoid, it is estimated that ~20.000 prisoners were taken here. Only 7 survived.

As pictures speak more than words, you can look with your own eyes at a few more here

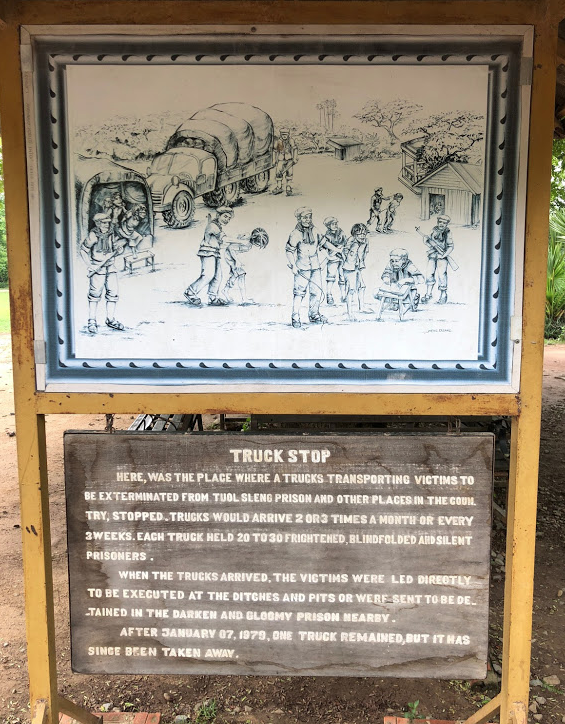

Choeung Ek: The “Killing fields”

As killing became a daily practice, you have to think about its practical consequences: it leaves behind heavy bodies, dirty smell, pools of blood, inconvenient proofs and a logistical nightmare. It was very messy to kill people in a school, and close to the city, so the Khmer figured out a different strategy: after the forced confession, prisoners were put in a van, tied and blindfolded, and told they were going to serve a prison sentence. Transportation happened at night, to avoid witnesses, and the trip to the killing fields was the last journey for tens of thousands people. Hearing the story, I sensed a eerie similarity with Nazism, arrenging the Jews’ trips to the concentration camps.

Except the killing fields, as you might have guessed, were not a place of forced labor, but a structured process to kill perceived enemies and get rid of their corpses. Far from any living center, a lot of empty spaces were devoted to digging holes and executions.

Upon arriving here, prisoners would’ve heard loud music celebrating the regime, and may have stayed in a hot building for just a few hours, before being brought in front of a ditch and executed. The loudspeakers were covering any noise for unsuspecting farmers nearby, and killing was another messy process. Given the disastrous economy and the high cost of bullets, prisoners were killed by clubs / spears / farming tools, with a slow and painful death. Children and babies, no matter how young, were smashed against trees before being thrown in the pits. DDT was used to cover the smell, ditches were refilled with soil on top of the bodies and new ones were excavated. It is estimated that ~9 thousand people found death here, and it’s only one of the many camps around Cambodia.

A long work of historians, doctors, and other experts identified countless skulls and bones, cleaned them and tried mapping down their death reason, but it’s almost impossible to determine the identities of people. A beautiful mausoleum (stupa) has been erected here, and it contains a some of the remains found.

No justice in history

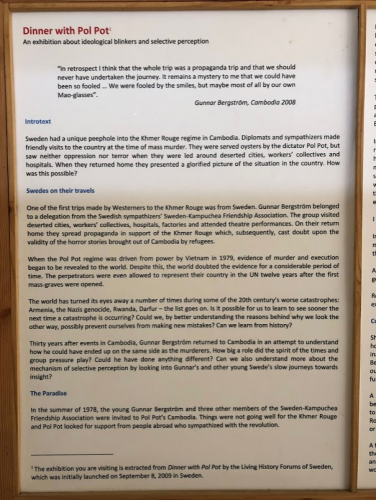

It’s something that historian Yuval Noah Harari says in one of his books, and I couldn’t agree more. After leading to the massacre of a quarter of his people in few years, Pol Pot and his close collaborators managed to escape and kept their power and status for many years. The “communist dream” was strong in many of the first world minds, and the Khmer Rouge had a seat at UN for many years, helped by the lies spread by collaborators and fans abroad (sic), like the Swedish delegations. Other political ties made it possible, like the help from China and some support of the US (!), opposing the Vietnam regime.

Only many years later the truth was found, a few people were processed, and Pol Pot died peacefully in his house, after only 1y of house arrest caused by a faction of his own Khmer Rouge. Most of the Khmer Rouge went away scot-free, enriched by the regime, and with great seats at the table of the new society.

One interesting testimony is from Sweden’s fans of the Khmer Rouge, you can read it below:

Hope

I promised a positive message, and there are many for sure. Cambodia seems to be now growing in population, economy and future prospects. Lots of time has passed, and I imagine that this nightmare feels like a very distant dream to most people. As I connected with the startup community in the country, I noticed a strong grit, and desire to improve life and be part of a global community. I feel the internet has helped unlock many opportunities for the new generations, and the country is very much focused on a bright future ahead. You need to actively search for its past, though as we learn or remind ourselves about it, we can avoid any of these nightmares from happening in the future.

End disclaimer

Note that I’m not an historian, this is my understanding from reading and visiting the country. If you notice any factual mistakes, feel free to flag them to me and I’ll update the article accordingly.

*While I believe the US support was undeniable, mine is a simplification of history and complex international politics, which goes beyond my knowledge (e.g. how Lon Nol got into power in the first place – the Cambodian coup of 1970). If you’re interested you should read about it from historians, and feel free to let me know about it.